Rome's disappearing shops & cafes

By Jeremy Bowen

BBC News, Rome

People in Britain often lament the changes in the nation's towns and cities, as more and more national and international chain stores, banks and coffee outlets force out local businesses and city centres all seem to look the same. But this is not just a British phenomenon. Jeremy Bowen says that Rome is also yielding to the relentless march of globalisation.

Romans still take their morning coffee and pastry at their local bars

It may be hard for many people who live in the teeming cities of our globalised world to understand, but my commute to work is one of the great pleasures of my day.

To get to the office, I walk for about half an hour through what must be the most beautiful city anywhere.

The centre of Rome is not remotely busy before 10 o'clock in the morning. The day feels fresh and new.

Even the Pantheon, the great domed building that started as a Roman temple 2,000 years ago and was preserved intact because it became one of the earliest Christian churches, is serene and cool when I walk past it.

The tourists must still be sleeping.

My most senior colleagues here say that the 1950s were better, before mass tourism, before there were many cars, when eating in a restaurant was cheaper than cooking at home.

But I suspect that, when I am old enough to be able to say it was better in my day, I might reminisce about Rome at the start of the 21st century.

Life may be less charming than it was in the 1950s but I suspect it is much more attractive than it will be 50 years from now.

Adverts on TV show happy Italian families eating something that mamma bought in the supermarket and warmed up in the microwave

The world is shrinking and it is squeezing everywhere and everybody.

Almost 25 years ago, I spent a year in Italy as a student. It was fascinating and fun, but no paradise.

It was still recovering from the turbulence of the 1970s, when there had been bombs, kidnapping and ideological conflict between the right and the left.

And it was very Italian.

Everyone had Italian cars - Fiats for the masses, Alfas for the sporty, Lancias for the rich.

On every corner of the city where I lived small shops sold salami, ham, cheese and wonderful fruit and vegetables.

Romans have a strong sense of their own identity and a huge pride in their city.

In bakeries, as well as bread there were strange flat sheets of dough, dusted with flour or knotted into little parcels. In Britain I had never seen fresh pasta.

Twenty-five years ago, not many foreigners lived in Italy and not many people spoke foreign languages nor appeared to have any desire so to do.

But now, in the globalised world, some middle-class Romans send their children to international schools so that they will grow up speaking English fluently.

The Italian father of one of my daughter's classmates speaks to his Italian children only in English.

In restaurants the waiters are usually Italian but, if you look into the kitchens, the people that are turning out local favourites like buccatini all'amatriciana or spaghetti carbonara are very often Asians.

And the way of life that seemed routine and ordinary 25 years ago is disappearing.

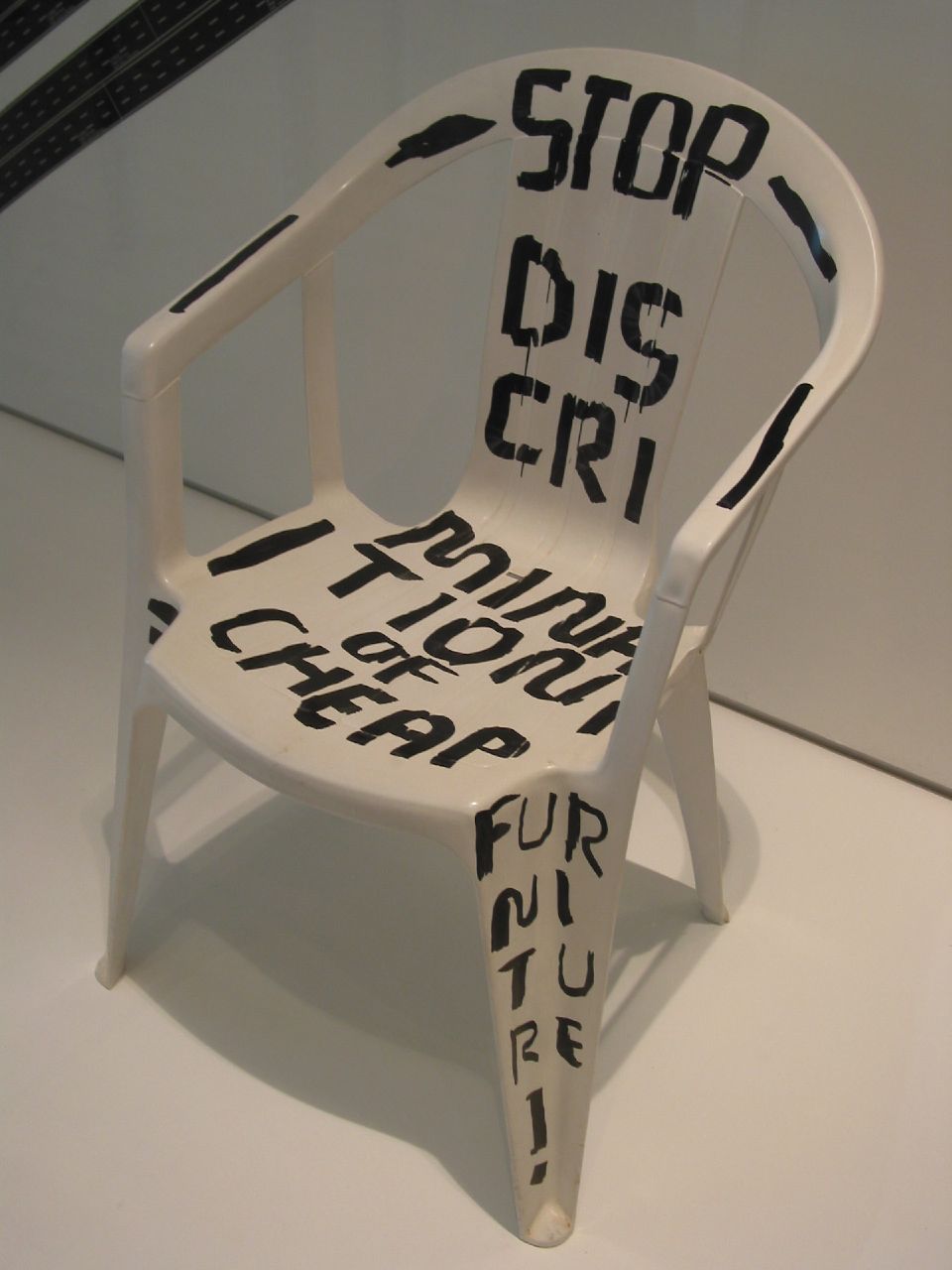

The businesses that paid for it - that produced things that people wanted to buy because they were well designed and well priced - are struggling to compete against cheap competition from China.

The wives and mothers, who would have spent the morning shopping and cooking, often go to work now.

Many of the small food shops they do not have time to visit any more have closed. Adverts on TV show happy Italian families eating something that mamma bought in the supermarket and warmed up in the microwave.

Sometimes on my way back from work, I stop at a poultry butcher who sells excellent free range chicken and eggs.

His brother sells the red meat at a shop just across the road. I have never seen any other customers in the shop when I have been buying my chicken.

Long before closing time, which is about 7.30 in the evening, the shop is immaculately clean and he is pacing up and down in the street outside, packed up and ready to go home.

All the shops like that seem to be run by men and women in their 60s, and most of them will turn into boutiques or jewellers' shops when their owners retire.

I do not want to overstate the sense of change.

Walking through Rome every day is a delight which I will never forget. There are still workshops in beautiful medieval streets fixing scooters or espresso machines, or making boxes or strange balls of wire.

The greengrocers - and there are still plenty of them - sell local fruit and vegetables that are in season, not tasteless cotton wool balls that have been flown in from the other side of the world.

Tourists can buy Big Macs to eat on the Spanish Steps but hundreds of thousands of Romans still take their morning coffee and cornetto - a kind of sweet croissant - standing at their local bars.

They have a strong sense of their own identity and a huge pride in their city.

But the commercial forces that are taking away too many of the differences that make the world interesting are at work here too. And it is a process that goes in only one direction.

BBC News, Rome

People in Britain often lament the changes in the nation's towns and cities, as more and more national and international chain stores, banks and coffee outlets force out local businesses and city centres all seem to look the same. But this is not just a British phenomenon. Jeremy Bowen says that Rome is also yielding to the relentless march of globalisation.

Romans still take their morning coffee and pastry at their local bars

It may be hard for many people who live in the teeming cities of our globalised world to understand, but my commute to work is one of the great pleasures of my day.

To get to the office, I walk for about half an hour through what must be the most beautiful city anywhere.

The centre of Rome is not remotely busy before 10 o'clock in the morning. The day feels fresh and new.

Even the Pantheon, the great domed building that started as a Roman temple 2,000 years ago and was preserved intact because it became one of the earliest Christian churches, is serene and cool when I walk past it.

The tourists must still be sleeping.

My most senior colleagues here say that the 1950s were better, before mass tourism, before there were many cars, when eating in a restaurant was cheaper than cooking at home.

But I suspect that, when I am old enough to be able to say it was better in my day, I might reminisce about Rome at the start of the 21st century.

Life may be less charming than it was in the 1950s but I suspect it is much more attractive than it will be 50 years from now.

Adverts on TV show happy Italian families eating something that mamma bought in the supermarket and warmed up in the microwave

The world is shrinking and it is squeezing everywhere and everybody.

Almost 25 years ago, I spent a year in Italy as a student. It was fascinating and fun, but no paradise.

It was still recovering from the turbulence of the 1970s, when there had been bombs, kidnapping and ideological conflict between the right and the left.

And it was very Italian.

Everyone had Italian cars - Fiats for the masses, Alfas for the sporty, Lancias for the rich.

On every corner of the city where I lived small shops sold salami, ham, cheese and wonderful fruit and vegetables.

Romans have a strong sense of their own identity and a huge pride in their city.

In bakeries, as well as bread there were strange flat sheets of dough, dusted with flour or knotted into little parcels. In Britain I had never seen fresh pasta.

Twenty-five years ago, not many foreigners lived in Italy and not many people spoke foreign languages nor appeared to have any desire so to do.

But now, in the globalised world, some middle-class Romans send their children to international schools so that they will grow up speaking English fluently.

The Italian father of one of my daughter's classmates speaks to his Italian children only in English.

In restaurants the waiters are usually Italian but, if you look into the kitchens, the people that are turning out local favourites like buccatini all'amatriciana or spaghetti carbonara are very often Asians.

And the way of life that seemed routine and ordinary 25 years ago is disappearing.

The businesses that paid for it - that produced things that people wanted to buy because they were well designed and well priced - are struggling to compete against cheap competition from China.

The wives and mothers, who would have spent the morning shopping and cooking, often go to work now.

Many of the small food shops they do not have time to visit any more have closed. Adverts on TV show happy Italian families eating something that mamma bought in the supermarket and warmed up in the microwave.

Sometimes on my way back from work, I stop at a poultry butcher who sells excellent free range chicken and eggs.

His brother sells the red meat at a shop just across the road. I have never seen any other customers in the shop when I have been buying my chicken.

Long before closing time, which is about 7.30 in the evening, the shop is immaculately clean and he is pacing up and down in the street outside, packed up and ready to go home.

All the shops like that seem to be run by men and women in their 60s, and most of them will turn into boutiques or jewellers' shops when their owners retire.

I do not want to overstate the sense of change.

Walking through Rome every day is a delight which I will never forget. There are still workshops in beautiful medieval streets fixing scooters or espresso machines, or making boxes or strange balls of wire.

The greengrocers - and there are still plenty of them - sell local fruit and vegetables that are in season, not tasteless cotton wool balls that have been flown in from the other side of the world.

Tourists can buy Big Macs to eat on the Spanish Steps but hundreds of thousands of Romans still take their morning coffee and cornetto - a kind of sweet croissant - standing at their local bars.

They have a strong sense of their own identity and a huge pride in their city.

But the commercial forces that are taking away too many of the differences that make the world interesting are at work here too. And it is a process that goes in only one direction.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home